Season content notes: internalized ableism, trauma recovery, cultural elitism

Paiokp’s fingers flashed. After so many hours, day after day, week after week, eir fingers knew this new work. Teaching themselves a new craft that no one had done before was hard. There were many mistakes, and undoing them was even harder than doing it in the first place. But it was possible.

Wrap the coarse yarn around thick fingers, slip the blunt needle through, under, over, around, slide one loop off the fingers, and put a new loop on. One knot at a time, the green circle between Paiokp’s hands grew. It was a small miracle, making something that had never existed before.

Practically, Paiokp knew, they all knew, this was a unique craft, and that uniqueness meant they could charge enough to be more than worth their time. But that wasn’t why Paiokp treasured it.

Paiokp loved the work. Loved not being surrounded by the smell of fish guts. Loved creating something beautiful. Loved the feel of the linen thread, coarse as it was, and looked forward to when ey was skilled enough to make something with the delicate thread which had been Kyawtchais’ courting gift. Ey tried not to think that ey would probably not be here to do so.

Starting from Paiokp’s net-making methods, they had slowly shrunk down the movements and altered the techniques to create something like a net without holes, a fabric that was a series of knots. Like net-making, they get the best results working in circles. From there, Paiokp had thought eir project obvious.

The great green circle was almost finished. In the dim light of the workroom, its varied shades gave it the illusion of moving. A forest on a windy day. Soon the blue ring around it would begin.

Kyawtchais, Silent-Spinner and newest to their strange pieced-together family, stopped Paiokp to run eir hands around the circle, smiling at something ey felt in the rise and fall of the texture. “It is good,” Ey said. “But it is heavy. Not good for clothing.”

Paiokp shrugged. Ey was from a fishing family. “The long-sail ship crews often speak of how cold it is on some of their journeys. I think they will like a heavy fabric sometimes.”

Lefeng, guarding-one, once-walker, agreed. “It is still lighter than leather, and much sturdier than normal fabric. My family would have used this. If we can ever figure out how to make clothing with it…” Lefeng wanted to make a shirt. It was slow. Lefeng insisted eir fingers refused to do as ey wished. For all Paiokp knew, ey was right. Certainly, Lefeng spent more time picking knots out of eir small practice pieces than making progress!

On Paiokp’s other side, Kyawtchais worked on a piece even larger than Paiokp’s circle. Kyawtchais, trying to get as comfortable with the new craft as ey was with spinning, was working on a rug. Or– Paiokp thought it should be a rug! The large project let em capitalize on the repetition that set the craft in their fingers. The wide oval wasn’t made with thread at all, but with a small coarse rope, barely the width of Paiokp’s littlest finger.

Kyatchais and Lefeng argued good-naturedly over what it would be as they worked. Lefeng, like Paiokp, thought it was sturdy and rough enough to make a good rug for the entrance area. They could clean their feet and shoes on it, and any wet would be absorbed into the rope instead of turning into mud on the floor. Kyawtchais wanted to use it as a spouse-gift to the Silent Spinners. Ey said the heaviness of it would make it a good blanket for those in eir former family who need to be ‘weighted down.’

Having seen Kyawtchais when ey was… not well, Paiokp understood what ey meant about being ‘weighted down’. But ey still agreed with Lefeng — that cord was too rough to be wrapped around anyone!

Kolchais had picked up the skill well enough. But the constant pain which kept em from being a runner like eir former family interfered with this too. Ey had to stop frequently, or eir hands cramped up and ey would need to stop for the rest of the day.

Ey paused now. Set the small piece aside — it looked almost like a cloth bracelet — and wrapped eir arms around emself, with eir hands in eir armpits.

This time, Kyawtchais put down eir work as well, went over to Kolchais, and pulled Kolchais’ hands out, chafing and rubbing them as if Kolchais had been too long in the water and grown chilled.

“You need to tell them.” The quiet voice made Paiokp jump and spin around. With Kyawtchais and Kolchais occupied, Lefeng had leaned closer and whispered in Paiokp’s ear.

“What?”

“You know what. I am not the fool you seem to take me for. You have made no commitments, no promises. Have not even gifted Kyawtchais with your name. Creating a new family was your idea, but you will leave, abandon us. All because of this village superstition you assume the city-folk share.”

Paiokp looked down, avoiding Lefeng’s too-seeing gaze. “Why haven’t you said something, then?”

“I am saying something.”

“I meant to them.”

Lefeng jerked back as if Paiokp had slapped em, stared a moment, then turned and continued working, this time with eir back to Paiokp. Paiokp had no idea what, if anything, that meant among the far-walkers, but they had all learned what it meant among the Silent Spinners, who spoke with hands as often as mouths. ‘I don’t want to speak with you.’

Paiokp sighed and went back to eir work. Of course, Lefeng didn’t understand. The barbarian was a good person, would make a good spouse and a wonderful parent to Chestef. But there were so many things ey didn’t understand about the way the world worked. Why was it ey could admit that ey didn’t understand money, religion, the working of the council… so many things… but on this one thing refused to listen? Instead, Lefeng insisted that ey was right and Paiokp, who had lived with the sun-curse for most of eir life, was wrong.

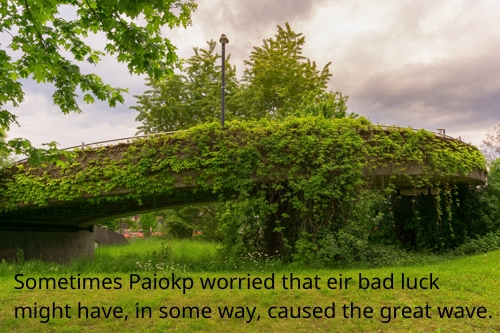

Lefeng hadn’t been there when Paiokp’s bad luck caused the fishing ground to fail 10 storm seasons back. Wasn’t there when eir family turned their backs on em after the death of eir cenn. Wasn’t there for… so many things. Sometimes Paiokp worried that eir bad luck might have, in some way, caused the great wave. But others before em had been sun-touched, and surely the wave would have come many times if it was a matter of bad luck. Surely that — all those deaths — couldn’t be eir fault as well.

Paiokp’s vision blurred and ey blinked away tears. The light coming through the screen had dimmed enough. Ey carefully rolled up the work and wrapped it up in a linen sheet. And then ey left.

Leave a Reply